A cautionary note to marketers and designers building automated experiences

Three years ago, my mother died.

In the days around her death, I was in New York with my sister. Like most people do now, I took photos of us together, of quiet moments, of the city moving on while our lives had just stopped. I didn’t take those photos to document grief. I took them because I didn’t know what else to do with my hands. And I am a creator. I photograph my life and often share it with you in ways I hope you find meaningful.

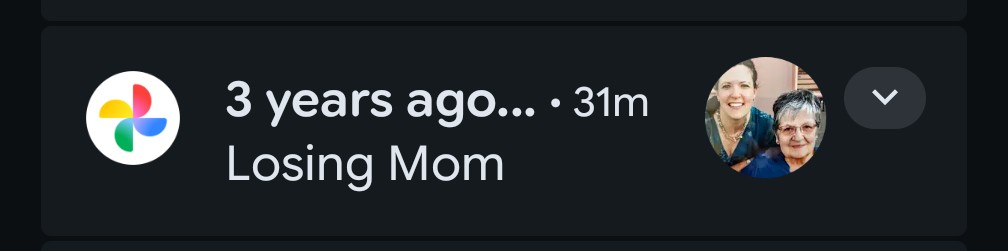

Then, Google Photos sent me a notification.

It had created an album for me. The title was: “losing mom.”

As a marketer, I immediately recognized what was happening. No human named that album. No editorial review by committee. No sensitive-content meeting. This was automation doing what we ask it to do every day: detect patterns, infer meaning, personalize output.

From a technical standpoint, it worked. From a human standpoint, it stopped me cold.

Because the thing is: the AI wasn’t wrong.

The photos were from the time my mother died. My sister and I did lose our mom. The system saw faces, timelines, metadata, and likely emotional signals, then connected dots I never explicitly labeled myself.

Out of curiosity, mostly, I opened the album.

The photos began playing as a slideshow. Soft, touching music faded in behind them. The kind of music we use to signal care, tenderness, meaning.

And suddenly this wasn’t just classification. It was an experience. I want to talk to the people who design these experiences.

When Inference Becomes Storytelling

We’re all comfortable with AI recognizing objects. Dogs. Beaches. Food. Receipts. That kind of automation feels helpful and low-risk.

But this wasn’t object recognition. This was life-event inference, followed by narrative construction.

“Losing mom” is not a neutral label like “Trip to New York.” It’s a deeply emotional, identity-shaping moment. And the system didn’t just tag it. It framed it, scored it with music, and presented it back to me as a story.

As marketers and UX designers, we do this all the time. We build journeys. We choose tone. We add music, pacing, copy, imagery. We decide when to surface meaning and when to stay quiet. And often, we do it with the best of intentions.

What struck me wasn’t that AI could infer grief. It was that it assumed it should act on that inference.

Inferring is one thing. Turning it into a branded moment is another.

When “Correct” Still Causes Harm

It would be easy to say, “This shouldn’t happen.” But that’s not quite right, and it’s not a useful takeaway for people building real systems.

The system didn’t hallucinate. It didn’t invent a loss. It reflected something true. That’s precisely why it’s uncomfortable.

In marketing, we often equate accuracy with value. Better data. Better targeting. Better personalization. After all, personalization is the future yes? Micro-targeting equals more sales. Our feeds are hyper-personalized, and we love it, right? Our FYPs get a lot of TLC.

But emotional accuracy without emotional consent can still hurt.

The slideshow wasn’t garish. The music wasn’t manipulative in an obvious way. It was tasteful. Gentle. Well designed.

And yet my body reacted before my rational brain could catch up. I did a double-take. I could not believe my eyes.

Grief doesn’t move on a predictable timeline. Sometimes you want to remember. Sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you’re just trying to get through the day. An automated system deciding, based on engagement logic or content confidence, that this is the right moment to wrap your loss in music is a decision with real emotional consequences.

For some users, that experience might feel comforting. For others, it could be deeply upsetting. Devastating even.

Optimization Isn’t Empathy

AI is very good at finding patterns. It is not good at understanding appropriateness. That’s where we humans should intervene.

Appropriateness is situational. It’s deeply personal. It depends on timing, history, and emotional readiness, things we routinely underestimate because they’re hard to measure and impossible to A/B test.

As marketers, we optimize for:

- Engagement

- Relevance

- Sentiment

- Reach

- Impressions

- Click-through

But none of those metrics capture “Was this the right thing to surface at all?”

Automation doesn’t hesitate. It executes. And when we give it the ability to infer meaning, it will use that ability unless we explicitly tell it not to. It doesn’t worry about alignment.

Adding music, narrative pacing, and presentation crosses a critical line: it assumes not just relevance, but emotional permission.

That’s a dangerous assumption. We allowed it.

Consent Is More Than a Checkbox

We tend to think of consent in product terms: terms of service, feature toggles, privacy settings.

Emotional consent is different.

I consented to my photos being organized. I consented to faces being recognized and organized. I did not think about the fact that I might be consenting to my grief being identified, titled, and turned into a cinematic moment, especially without a way to opt out of that category of experience.

“Hey Sue, check here if you want us to remind you when your mother died,” was not an option.

For those of us designing automated journeys, this raises uncomfortable but necessary questions:

- Should systems narrate inferred life events at all?

- When does personalization become intrusion?

- Should we assume past moments and memories are always things to be celebrated?

- Which insights should remain silent unless explicitly requested?

- Are we designing for “most users,” or for users at their most vulnerable?

Designing for the Hardest Moment, Not the Average One

Here’s the challenge I think marketers and UX designers need to sit with:

The moments that matter most are often the moments when users are least able to protect themselves. Grief. Illness. Loss. Trauma. These are not edge cases. They are universal human experiences, and they are exactly where well-intentioned automation can cause the most harm.

If we want to build truly human-centered systems, we may need to:

- Treat inferred emotional states as private signals, not activation triggers

- Default to silence instead of storytelling for sensitive life events

- Give users control over themes, not just features

- Design escalation paths that require explicit invitation

- Accept that some data should inform systems without ever being surfaced

None of this makes the technology less powerful. It makes it more responsible.

Things to Ponder

I didn’t delete the album. But I didn’t watch the slideshow again either.

It sits there now, accurate, beautifully rendered, and deeply unasked for. Much like grief itself.

AI is getting better at seeing our lives. Our patterns. Our losses.

For those of us building automated experiences, the next challenge isn’t whether we can detect meaning. It’s whether we know when to act on it.

And whether we’re willing to design systems that sometimes choose to do nothing at all.